The Shah Cheragh Mosque: An Eye-Opening Solo Visit

What’s a restless tourist to do in Shiraz on a Friday night? The quiet in the old part of the city was a bit unsettling; everything east of the Vakil Bazaar on Lotfali Khan e-Zand Street seemed to be closed. Armed with my compact camera, I headed out of the hotel and into the chilly street, towards the only place that I knew to be open: the Shah Cheragh mosque.

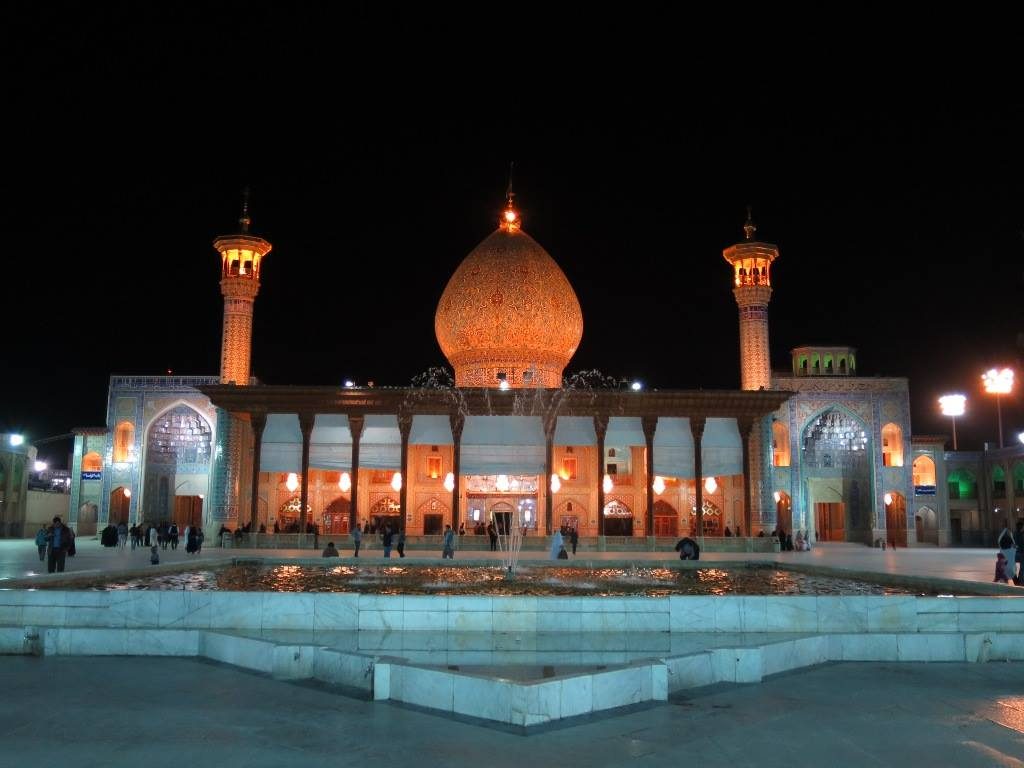

The dome of the mosque and its minarets was unmissable above the apartment blocks. I thus followed it down the side lane, where a signpost in English confirmed that I was heading in the right direction. It opened into a parking lot; a discreet gate beckoned from the opposite end. Equally discreet was the guardhouse next to it.

My visit to Shah Cheragh

The Greeting

Two men in uniform emerged from the box as I approached the entrance.

‘Salam,’ I turned to them and greeted. ‘May I visit?’

‘You tourist?’ They signalled to me to spread my arms, then gave me a quick frisk. It’s not the sort of warm welcome I’ve received at other mosques. Shia shrines like Shah Cheragh have been targeted by terrorists for years, however, so I expected and understood the treatment. For a fleeting moment, my faith in the famed Iranian hospitality waivered.

‘Wait here,’ one of the guards instructed with his hand when the pat-down ended. Was he satisfied? What awaited me? All this time, I held my compact camera in my hand but he and his colleague didn’t seem to notice. So much for the warnings from other bloggers about photography being illegal.

A couple of minutes of silence followed before a middle-aged docent wearing a sash walked casually towards me. He was to be my chaperone for the evening. Our greetings were a touch stiff, but as we walked into the courtyard, he described the history of the site in a low and gentle voice.

The History of Shah Cheragh

The Shah Cheragh complex is a mausoleum which houses the shrines of Ahmad bin Musa and Muhammad bin Musa. They were the brothers of Imam Reza, the eighth Imam; all of them were descendants of the prophet Muhammad (P.B.U.H.). Ahmad and Muhammad were martyred in Shiraz during the persecution of Shia Muslims by the Abbasid Caliphate, which, according to Shia belief, also ordered the Imam assassinated.

The mausoleum did not come into being until, in 1281, the Salghurian rulers discovered a body wearing a ring inscribed with Ahmad’s name. According to the legend associated with the discovery, the grave emitted a green glow (hence the name Shah Cheragh, or ‘The King of Light’) and Ahmad’s body was incorrupt. More unexplained miracles followed after the governor built the first shrine on the site. It has thus become one of the most popular and important pilgrimage sites in the country.

Future rulers of Iran renovated the mausoleum over the centuries, sometimes out of necessity due to destructive earthquakes. The present structure dates from the 19th Century, while the turquoise dome is about 60 years old. A bazaar once separated the shrines of Ahmad and Muhammad, but that has long made way for the massive courtyard that the two buildings now share.

Note: I forgot to ask about how Muhammad’s tomb was found, so if you do visit Shiraz, please ask your docent and let me know.

Inside the Mausoleum

My docent and I went into the larger Shah Cheragh mausoleum first. Despite the wintry chill, the thick carpets made walking barefoot more comfortable than I expected. The ornate gold and silver doors were open but a black shroud kept the interior hidden from view. Now and then, gaps would appear as worshippers slipped past it to reveal glimpses of the inside.

And what a gem that shroud hid. Mirror tiles scattered the light of the chandeliers in all directions. They created thousands of twinkling stars on pillars and the vaults. If this was meant to simulate the cosmos, it was on point, and I was dazzled.

As I faced the walls, my reflection as I knew it ceased to exist; each subtly-angled surface on the walls rendered it to pieces. This wasn’t a place that indulged vanity and mirror selfies. It every-so-slightly nudged my mind away from worldly thoughts. Whispered prayers echoed around the hall and blended into one another; those drew my mind towards the celestial.

That all this was put together by hand, long before the age of computers, made it even more impressive, as my docent reminded me. I recalled the contributions of mathematicians from this part of the world, which only bolstered his claim.

The Tomb of Ahmad ibn Musa

The tomb of Shah Cheragh took pride of place in the centre of the hall of mirrors. It was a tall silver reliquary, about three metres high, with arched windows. Inside the structure, a shallow moat of Iranian rial bills surrounded the casket. Calligraphic inlays adorned the polished wooden surfaces while a Quran rested on a bookstand at its head. Two sides were accessible to worshippers on our side of the hall; a long screen separated the other two and the women’s side of the hall.

All around the tomb, pilgrims closed their eyes and rested their palms on the grille that separated them from the shrouded casket within. Sometimes, they left offerings for prayers that were answered. When the faithful were done, they did not turn around; they backed away slowly, being careful to avoid showing their backs to the tomb.

I asked my docent if I could take a few photographs. With his consent, I found a few corners to take discreet snaps from a distance. As with the visa process and a few other things in Iran, I’d read different accounts on the internet and was glad that I got lucky. If anyone noticed me and my little Powershot, they did not raise a ruckus.

Elsewhere on the Grounds

Away from the tomb of Shah Cheragh, some of the men sat on carpets and meditated the Quran. Others prostrated in prayer with their foreheads to pieces of clay called mohr. We took a walk around the mosque proper behind the shrine, a large and unremarkable hall that was renovated within the last thirty years.

The tomb of Muhammad ibn Musa was similar to that of Shah Cheragh, though my docent showed me that other eminent figures were buried with him under the same roof. A couple of them were martyrs in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Their tombs were modest, being “just” ornate slabs under plexiglass covers.

As with the many other things that I was fortunate to experience in Iran, it was an eye-opener. My Muslim travel buddies were not with me at the time, but these were not practices that they followed back home, where the majority of the Muslims are not Shias. I write this not to put down or legitimise any group, judge their beliefs or create divisions (and I will delete any incendiary comments). It’s a sharing of what I observed – the works of a group of pious Muslims who have different interpretations of the teachings they received.

A Tricky Exit

The complex also houses a library and a museum on the south-western side of the courtyard. Being evening and Friday in particular, there was no way I could visit them. I sort of knew that my tour of Shah Cheragh ended when my docent engaged in conversation in Persian while I watched the people around me. We parted ways, but not before both balding men turned to me to ask if they should consider hair transplants. They’d been nothing short of polite throughout my time there, but what a random way to part company.

I left them with these wise words: Acceptance is cheaper.

The docents returned to their office, while I followed the signs to the other gate of the mosque, eager to see if it differed from the side I entered. It led to a parallel universe filled with the noise of engines and pilgrims either getting out of cars or entering them. Soldiers with assault rifles kept a watching brief on the crowds that passed through the gates. Unable to figure out how to get back to the quiet boulevard my hotel was on, I turned back.

I approached the guards and tried my best to explain that I only wanted to get to the other side. The reply came in the form of another pat-down. One of them pointed to my camera and suggested that I leave it with them.

Oh, crap. I wasn’t going to get anyone look through the photos on their own. I repeated, with a smile, that I was only passing through – and that was how I received an armed escort for the first time in my life. It ensured that I left the mosque without incident a second time.

Directions & Details

Shah Cheragh appears to be open all day and night, every day, to pilgrims. The main gate is at the intersection of 9 Dey Street and Hazrati Street. Taxi rides within the city are inexpensive anyway, but get an idea from your host or hotel first of how much you should offer the driver to get you there from your pick-up spot. Admission is otherwise free. Men should at least wear trousers and cover their shoulders, while women may borrow a chador at the entrance. It’s a large, loose cloth that covers everything but your face.

The car park entrance that I took is walking distance from Nasir ol-Molk mosque; follow Lotfali Khan e-Zand Street west for about 180 metres, until you see the sign in English that points into the side lane. (If you’re walking in the other direction, the lane is 150 metres past the entrance of the Khan madrasah on the opposite side of the street.) The domes should be visible once you pass the houses on the right.

If you’d rather not deal with armed guards and patdowns outside airports, you may visit the Imamzayeh Ali ibn Hamze near Hafez’s tomb instead. It features a mirror-tiled shrine too, and photography is explicitly allowed there.