Cologne Cathedral: One Look Isn’t Enough!

It was impossible to ignore the Kölner Dom when I first stepped out of Cologne’s central station. How could I, when it’s such a massive structure? The sunken plaza that I stood in only served to exacerbate the impression of size. It has its advantages, though; in the height of summer, its shadow offered the people gathered on the steps of Domplatz respite from the heat.

My eyes ran over the masonry. From the roof, flying buttresses flowed down the blackened walls that witnessed the bombing of the city in World War II. Here they still stood, even after the Dom took 14 hits. On the western facade, the two soaring spires form an unmistakable landmark. Figurines of holy men and women filled the niches in the doorways, while the arches and windows pointed heavenward towards finials several stories above.

If you think that the construction of Barcelona’s La Sagrada Familia is taking took too much time, wait til you find out that it took more than 630 years to complete Cologne’s cathedral. Work started in the year 1248, then halted in 1473. The spires were only built between 1848 and 1880. Even then, like Gaudi’s work, it seems to be perpetually under renovation. The scaffolding on the north spire never seems to go away, except with the help of Photoshop.

Inside the Dom, the piers seem to go on forever

The impression of height continues with a choir that has a height-to-width ratio of 3.6, which is greater than any other mediaeval church.

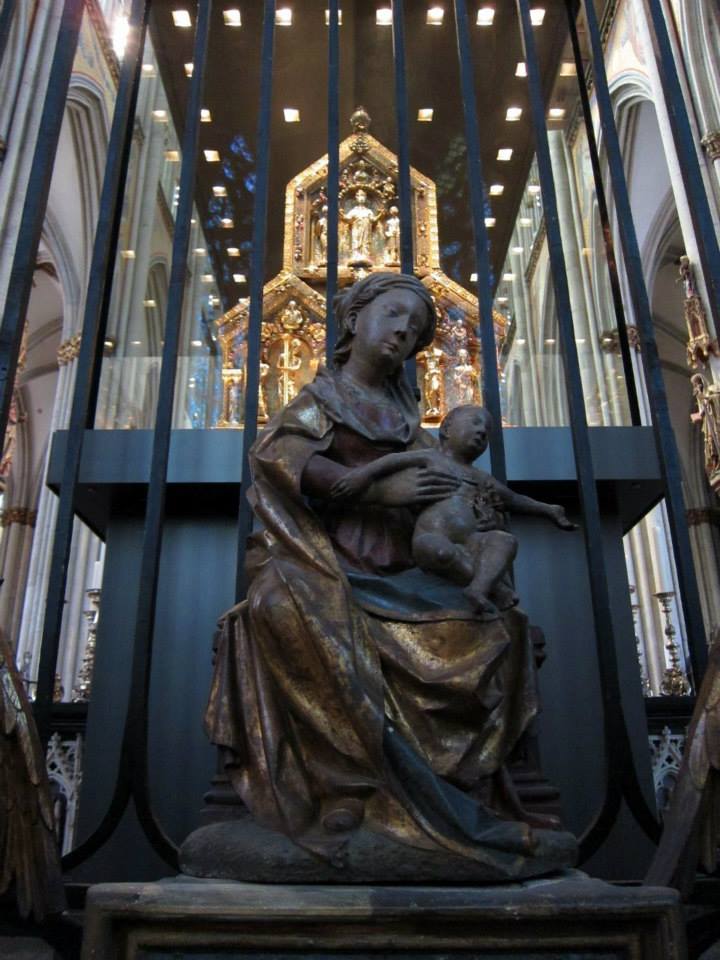

On the high altar, the pride of place goes to the Shrine of the Three Kings. The gold-plated reliquary contains the bones of the biblical Magi, the Eastern wise men who travelled to Bethlehem to pay Jesus homage on that first Christmas. It’s a treasure of the city that Archbishop Rainald of Dassel brought back from Milan as a gift from Emperor Frederick Barbarossa.

Behind the glass walls of the cabinet, figurines depicting the prophets and scenes from the life of Christ adorn its gold-plated surfaces. Emperor Otto IV provided the gold, silver, cameos, and jewels that form the images and fill the spaces between them.

Elsewhere, ornate chapels, altars, reliquaries, mosaics and tombs load the mind with an excess of classical beauty.

It may seem excessively lavish, even vulgar, but the following passage nails the counter-argument:

‘A church for the poor should not look impoverished. It is one of the few public buildings that those without status or money should be welcome to enter. The poor may not often visit the art museum, the symphony hall, or the stately hotel. However, a worthy church can give the poor the same experience of art, fine music, and nobility that the rich and middle class are happy to pay for. And in thisway the Church acknowledges that high culture should be even for the those who have nothing.’ – Duncan Stroik, How to Design A Church for the Poor (Aleteia, 15 September 2014)

Indeed, admission is free, as it has always been.

Compare: 25 Churches in Rome to Visit for Art, Beauty and History

How’s the view of Cologne from the top?

While it costs nothing to admire the art, getting exercise via climbing the steps costs 4 EUR. K and I climbed all 530 steps to the top of the south spire in the height of summer.

The view of Cologne from the top made the hard slog up the narrow staircase worthwhile, however. Cruise ships full of pensioners plied the river Rhine, passing the crane buildings along its banks. It’s a nice way to spend one’s retirement, though that’s not how I want to spend mine.

There was also a noticeable contrast between the concentration of (restored) mediaeval buildings within and outside the Altstadt. It’s a stark reminder of what was lost during the 262 bombing campaigns by the Allies. Modern and post-modern structures, built with different sensibilities in mind, have since taken their place.

However, the best views are to be had in the evening

Taking a good picture of the Dom from its base was a futile exercise. It was simply too large; any photograph taken even 100 metres away squashed the towering spires. It also took away the experience of straining one’s neck that was an essential part of the experience. I needn’t have gone through the discomfort.

After the sun went down and I parted ways with K, I crossed the Hohenzollern bridge, passing the girders full of padlocks and the occasional train. Floodlights transformed the cathedral, throwing a ghostly white light on its sooty surfaces. The scaffolding was less of a bother from here, as was the bright blue light of the opera house.

From this distance, I could admire its proportions in a way I couldn’t in the morning from the train station. It’s one of those things that makes good city landmarks endearing. One look isn’t enough; you have to take them in from different angles and distances, and each time, it rewards you with something new. And that’s how it has stayed with me.