4 Haunting Ruins of Beijing’s Old Summer Palace a.k.a. Yuanmingyuan

One hour. That was all the time I had to venture beyond the conference venue and explore Beijing. The backpacker in me found it difficult to accept the reality of business travel.

Luckily for me, the Old Summer Palace (圆明园; Yuánmíngyuán) was a brief taxi ride from my hotel. Since I’d visited the other major attractions on a school visit years ago (including the UNESCO-listed Summer Palace or 颐和园), I wasn’t fussed about skipping them.

(Any information on those places that I still remember is probably outdated. Feel free to read about them on other blogs if you wish.)

The Old Summer Palace grounds open at 7 a.m. daily, and I had to return by 8.30. It would’ve been impossible to see the entire site, not even before the crowds arrived; after all, it’s the size of five Forbidden Cities. However, in my head, an hour was enough to see just the section that interested me the most: the Western mansions (西洋楼; Xīyánglóu).

The Sad History of the Old Summer Palace a.k.a. Yuanmingyuan

The Old Summer Palace is not exceptionally ancient by Chinese standards. It was built by the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty and expanded by his successors, making it “just” 300 years old. The Western mansions, in particular, are intriguing as the Qianlong Emperor commissioned Italian and French Jesuit priests to design them and supervise their construction. Their influence is evident in the architecture, but more on that later.

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, British and French troops led by Lord Elgin (his father acquired the Elgin marbles) looted and burnt the palace in retaliation for the torture and execution of their envoys. The Eight-Nation Alliance razed it further during the Boxer Rebellion 40 years later.

Future civil wars, the Cultural Revolution and nearby building activity took a further toll on the site. To the Chinese, however, the ruins remain a symbol of humiliation by foreign powers. Attempts to conserve them, restore them or replicate the original structures elsewhere always start heated debates. Collectors who refuse to return plundered treasures inevitably incur the wrath of the entire nation.

Such emotions and reactions were the reason I visited the palace. I sought to understand what China – and the wider world – lost through its destruction.

Getting There

To get to the Western mansions, I asked the taxi driver to take me to the eastern entrance of the Palace, not knowing if I was going to find a ticket office there. Thankfully there was one; more importantly, it was also open. I bought an extended ticket and marched through the iron-barred gate, 25 RMB lighter.

Looking at the sun is never advisable, but on this freezing, foggy morning, the pollution cut out the worst of its glare. I could well have been walking through Silent Hill; such was the smog’s effect. Despite that, there were still several elderly ladies and gentlemen brisk-walking and exercising in the outer park.

The Chinese erected a statue of French author Victor Hugo for his criticism of the razing of the Palace. He wrote, ‘Two robbers breaking into a museum. One has looted, the other has burnt. (…) one of the two conquerors filled its pockets, seeing that, the other filled its safes; and they came back to Europe laughing hand-in-hand. (…) Before history, one of the bandits will be called France and the other England.‘

Once I was past the gate to the mansions, however, I had the place virtually to myself. There were only two sets of footprints in the frost; one belonged to me, while the other belonged to the groundsman. The walk from the eastern entrance to the mansions took just five minutes, but it felt like I had entered an entirely different world.

The ruined buildings of Xiyanglou

Dashuifa

Dàshuǐfǎ ( 大水法) was the first of the ruins to come into view. The columns and arches that remain standing today were part of a large fountain that the Jesuits designed. In the photo, you won’t see the rail separating me from the rubble, but that and the empty pool made the site resemble an abandoned zoo enclosure.

Carved marble replaced the painted timber and brick that usually features in Chinese architecture. One doesn’t typically see Rococo facades in this part of the world, but the stylised cloud, flower and wing motifs in the masonry were unmistakably Chinese. Here’s what it used to look like:

By comparing the images, you can tell that Westerners weren’t the only ones who inflicted damage over the last 150 years.

The remains of a throne stood opposite the fountain. Called Guānshuǐfǎ (观水法), the emperor would sit here to admire the fountain. Today, what’s left of the wall is also worth a look.

Haiyantang

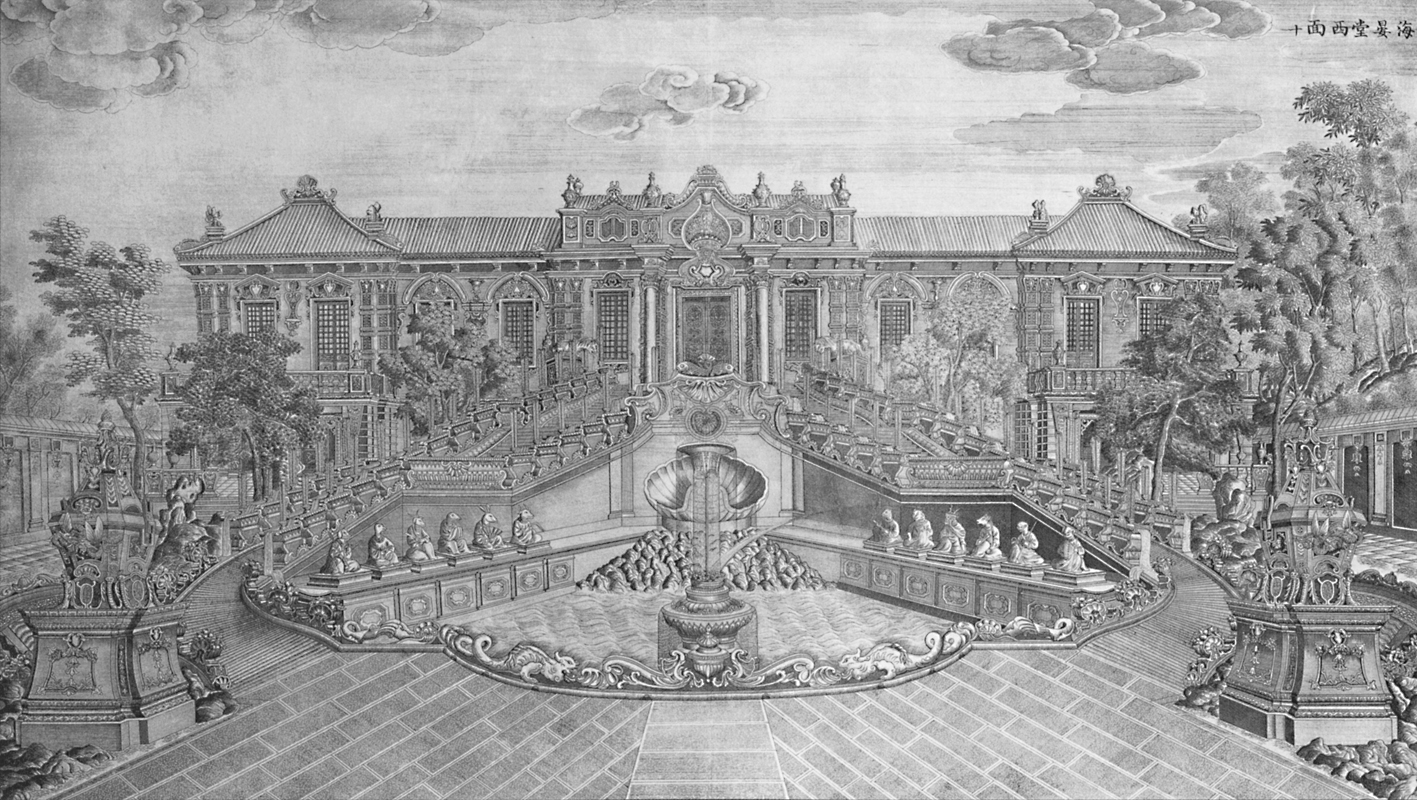

I headed west along the path, past the cafe, which led to Hǎiyàntáng (海晏堂). It was a huge water clock, designed by Michel Benoist, that spouted water from 12 zodiac animal-headed bronze figures.

Today, they’re no longer there; the French and British troops took them home as war booty. Two of the heads ended up in the collection of fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent.

The Chinese managed to get seven heads back, including those in Saint-Laurent’s collection, and they are in three museums around Beijing. They are still actively seeking the return of the remaining five. Visitors to the palace, like me, have to contend with replicas of the bronzes in the exhibit next door. Frankly speaking, they look sad in their current setting.

The effect was probably intended. The ruins, the replica fountain and the exhibits in the gallery were a powerful statement of the humiliation that the country experienced. The reluctance of foreigners to return looted bronzes and porcelain pieces only aggravates the resentment.

Huanghuazhen

Huánghuāzhèn (黄花阵) was probably the only structure that resembled how it looked ages ago. On Mid-Autumn Festival evening, the emperor would sit under the gazebo that overlooked the maze and wait for his concubines to find their way to him. The sight of thousands of lanterns threading the maze must have been marvellous.

The site was actually undergoing renovation, so I went through the workers’ entrance to take a quick snap. While it was a Sunday morning, I don’t think it was meant to be left unguarded.

Xieqiqu

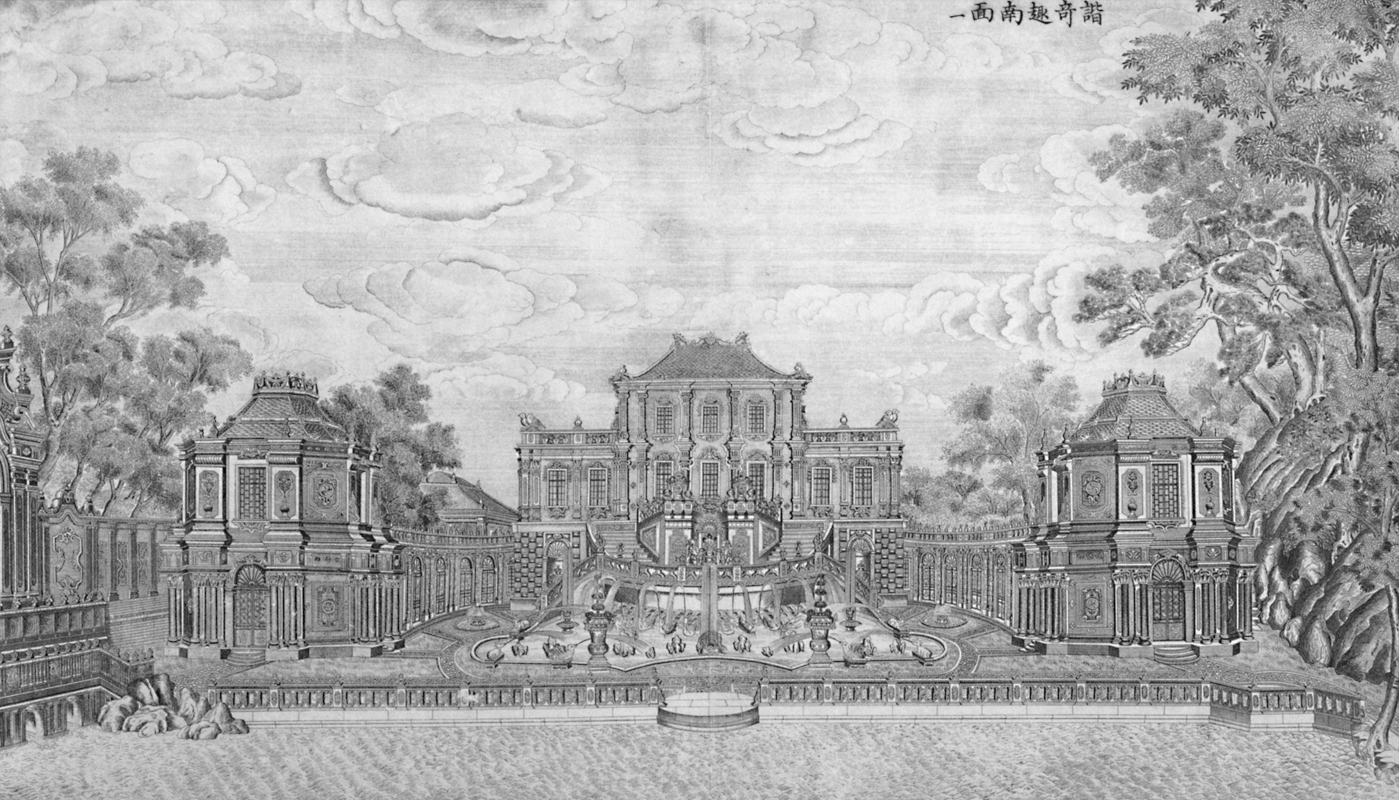

At the end of the compound stood Xieqiqu (谐奇趣), China’s first European-style water feature. It used to be a magnificent mansion, as the Jesuit priest Giuseppe Castiglione documented in this engraving:

The Second Opium War reduced it to this:

This sight was all that remained in 2016. At least the fountain had water in it.

This was the closest that I could get to any of the ruins of the Old Summer Palace and the details on the rubble:

There were several more magnificent buildings on the site, such as an aviary for rare birds. They were, unfortunately, unrecognisable piles of debris, stripped of any detail that might point to their former glory; hence, I did not document them here.

With 15 minutes to spare, temptation got the better of me. I could see Fuhai (福海), the largest lake on the palace grounds, just beyond the hedges. The inability to see the islands and bridges clearly came as a slight disappointment. However, I considered it as a bonus that was even able to see it at all.

With time running out, I made a beeline for the eastern entrance and caught another taxi back to the hotel. I’d accomplished my mission of sightseeing on my business trip, but sadness filled me. Visits to sites where willful cruelty and destruction took place tend to do that.

Closing thoughts

If you would like to read more about the Old Summer Palace and its sacking, I recommend reading the linked MIT Visualizing Cultures essays. They are far better than the Wikipedia entries.

As long as the ruins stand and the Chinese attach a lot of nationalistic pride to them, they will remain a powerful tool for propaganda. To me, however, Yuanmingyuan was also a physical reminder of a time of greater openness and collaboration between the Occident and the Orient. The cultural exchange resulted in secular architecture like none other. Its destruction was not just China’s loss; it was also humanity’s loss.

Ruins in Europe: See the remains of the Roman Empire in Trier